Turn End: quiet radicalism in Buckinghamshire

9 Townside, Haddenham, Aylesbury HP17 8BG, United Kingdom.

Year first built: 1960s

Historical Period: Post War

Architectural style: Modernist / Modern Vernacular

As part of our ongoing CPD into historic homes, we visited the inspiring post war modernist set of houses at Turn End.

So far we have visited all of the other lovely homes below:

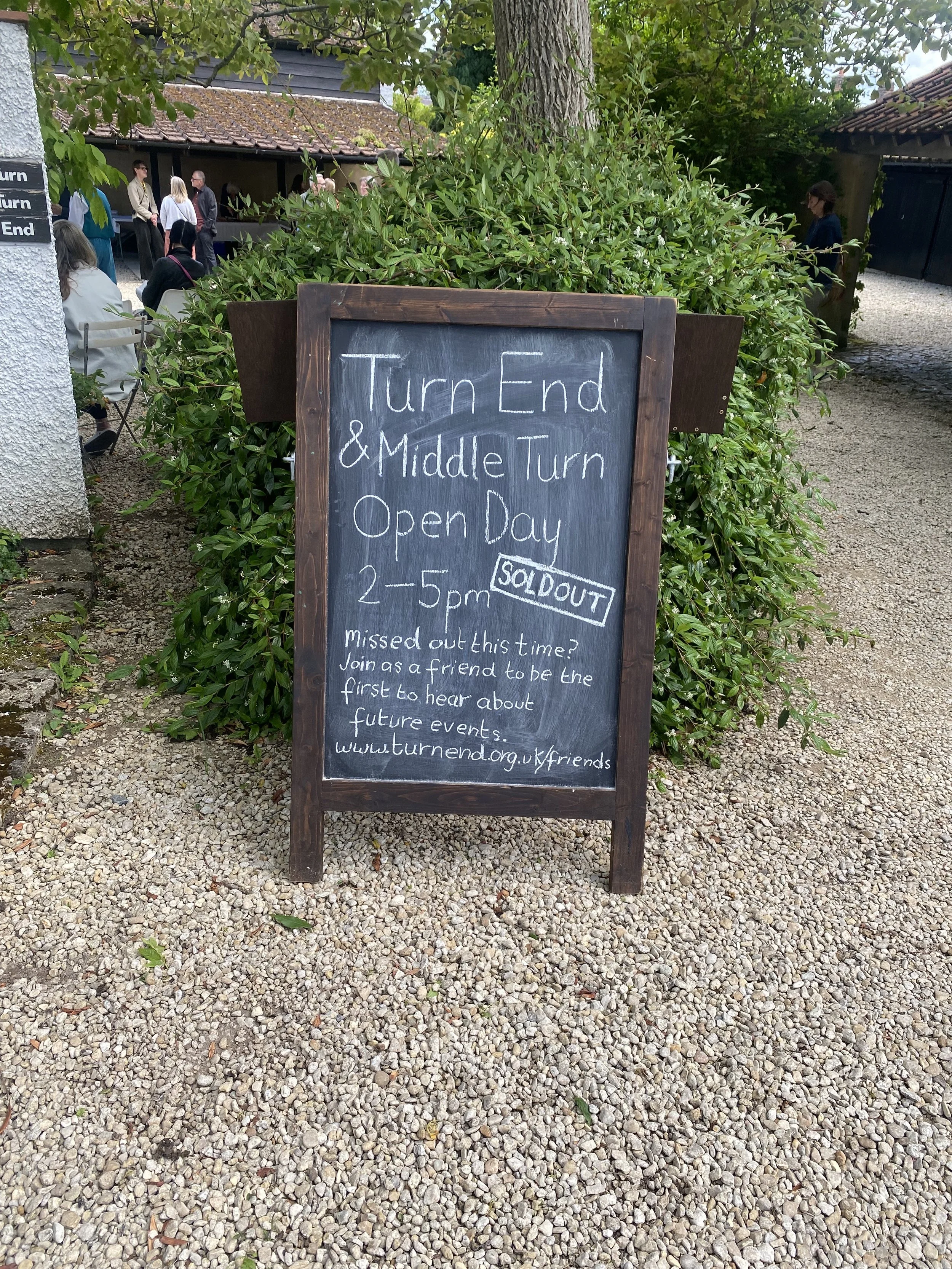

Once a year, the Grade II * Star listed Turn End houses open their doors to the public.

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1375663

We had been very lucky to get a last minute cancellation ticket for our family of four. Stepping off the train at Haddenham and Thame Parkway, under an hour from Marylebone, you begin the familiar suburban march. A small motorway, then a housing estate. Google Maps urges you on. Then, quite suddenly, the housing estate gives way to a quieter lane, and through a low flint wall and the branches of a large tree, you see a wide opening that feels different. It is calm, but not showy. You cross the threshold without quite realising it. This is Turn End.

When we visited it was busy, full of people chatting, queuing, comparing notes. The majority seemed to be architects, many clearly visiting as a kind of pilgrimage. It wasn’t hushed or reverent, but lively and full of energy, the way a beloved place should feel. A house, yes, but also an idea, a legacy and a lived conversation.

the open plan kitchen, living and dining areas

Designed and built in the 1960s by Peter and Margaret Aldington, Turn End is not just one house, but a cluster of three: Turn End, Middle Turn and The Turn, nestled into a former orchard in the centre of Haddenham. The houses sit within a walled garden, low and quiet, in dialogue with the village rather than in contrast to it. Everything is modest in scale, but exact in intention.

[Insert Image: Site plan showing three houses within former orchard]

Each house has its own identity, but together they form a coherent group. Turn End, the home Peter and Margaret live in, sits at the back of the site, facing a garden designed to unfold in sequence. The layout is clear, but it avoids symmetry. You move through the house as you would through a landscape; levels rise and fall, spaces expand then narrow, and light shifts from one surface to the next.

The rooms are not large, but the movement between them gives a sense of openness. Sound and light are as much a part of the experience as brick and timber. You hear birdsong and the crunch of gravel. You see shadows cast by leaves on lime plaster.

the courtyard at Turn End house

framed view of an ancient tree

There is no hierarchy of finishes. Materials are natural and local; brick, timber, lime and slate. A deep lintel above a small window. A timber bench set into a wall. Windows are positioned with care; a low opening catches the soil of the garden, a square pane frames a tree trunk, a skylight draws light across a white wall. Every detail seems quiet at first, but layered with thought.

The Aldingtons

Peter and Margaret Aldington were in their early thirties when they began designing and building Turn End. Peter studied at the Oxford School of Architecture (now part of Oxford Brookes University), graduating in 1956. His early career included formative years working for the London County Council, a progressive body that employed in-house architects to shape the capital’s postwar future. He later joined the practice of Frederick Gibberd before founding his own studio, Aldington and Craig, in 1961.

Margaret worked as a nurse and, unusually for the time, bought the Haddenham site in her own name and financed the build. The couple were not just collaborators in life but in construction, laying bricks, casting concrete, and building the houses by hand with minimal help. Their approach was practical and idealistic, shaped as much by early modernist thinking as by a deep care for place, landscape and economy.

Together, the Aldingtons created not just a home but a way of living - modest, thoughtful and generous, that continues to inspire architects and visitors to this day.

A conversation with the village

Haddenham is full of ancient flint walls, low barns, and small irregular houses, many thatched or timber framed. The Aldingtons wanted their houses to feel like they belonged. The materials are plain: redwood timber, concrete blocks, rough cast render, terracotta style concrete tiles. The forms are unassuming. The houses settle into the site rather than rising from it.

The use of wychert existing walls and chunky timber visible structures isn’t just aesthetic, it reflects a deep understanding of Haddenham’s vernacular palette and ensures that the houses sit gracefully alongside their older neighbours.

And yet, Turn End is no exercise in mimicry. It is listed Grade II*, a rare designation for a postwar home, because it manages to be both completely modern and completely of its place. It bends to the orchard that once stood here. It accommodates the footpaths, the neighbouring buildings, the trees, the weather. It is both site specific and timeless.

This close attention to village morphology, to the orchard's retained trees and Haddenham's medieval street grain, reflects a conservation mindset ahead of its time. It supports the principle that good design in sensitive locations grows from its surroundings, not despite them.

[Insert Image: Plan overlay showing original orchard/tree positions with house layout]

A long fight to build

Margaret bought the site in her name and paid for the build. The land came with planning permission for a standard set of developer homes, which would have involved flattening the garden and removing the mature trees. The Aldingtons had other ideas.

They spent 15 months in planning battles, refusing to bow to the expectations of bungalows and road widening schemes. The local authority was keen to take a portion of the land to expand the road. The Aldingtons argued for the integrity of the orchard, and for a new way of living within the village grain. The appeal escalated, even reaching the head of RIBA who intervened. Eventually, the couple won.

Their success preserved more than just their vision. It helped retain a piece of the village's natural and built heritage, defending what we now call local distinctiveness in conservation planning.

Their 15-month planning battle helped preserve the integrity of the site, not just for themselves, but for the village. An excellent example of what we now call community-informed conservation.

[Insert Image: Letter or document from the planning appeal or RIBA intervention]

Self build - Built by hand, with heart

They did not hand the drawings over to a contractor. They built it themselves. Together, they spent their days casting concrete foundations, laying blocks, hoisting lintels. Margaret was the labourer and financier. Two Oxford students came one summer to help finish it.

This was not their first time building with their own hands. Peter’s first commissioned house, designed for a couple he met through rock climbing, was also built by the pair. The idea of making, not just designing, was at the heart of their work.

At Turn End, the three houses went up together. The site was small, the forms simple, but the planning was nuanced and clever. Every angle seems inevitable in retrospect. It is one of those rare built projects where the plan and the place are in complete agreement.

[Insert Image: Axonometric or hand-drawn site plan showing all three houses]

Materials

the original wichert wall incorporated into the studio

The materials at Turn End are not lavish or decorative, but they carry a quiet strength. Each one has been chosen for its availability, its honesty and its relationship to the site. Many are local, some are salvaged, and all are used with a clarity that feels architectural rather than ornamental.

The walls are built from Durox aerated concrete blocks, chosen for their lightness and insulating properties. These are coated in a roughcast render, painted white, giving a texture that catches shadows and softens the building’s mass. The roofs are clad in Redland Delta tiles - concrete, not clay, though they read as terracotta from a distance. The effect is practical and warm.

Openings are framed with redwood; the window boards, cills and exposed rafters are all cut from the same timber. Above the front door, a solid Douglas fir lintel spans the opening with quiet presence. These details repeat gently through the house, giving it rhythm and coherence.

Underfoot, there is a confident plainness. The flooring is made up of twelve inch square quarry tiles in an earthy orange, laid flush and unvarnished. Outside, the paving is formed from local stone, much of it dug directly from the site during construction. The boundary walls are partly wichert, a chalky local earth mixture preserved from the original orchard plot and retained with care. These form parts of the house including the studio walls.

There is no ornament, but the materials speak. They tell you how the house was made, and with what. They connect you to the soil beneath your feet, the trees in the village, and the quiet logic of building only what you need. Turn End shows that material simplicity can be an aesthetic in itself, and a deeply sustainable one.

A family home

The living room area, painted concrete blocks form the sofa area

Peter and Margaret went on to raise their two daughters, Clair and Rachel, in Turn End. The house flexed around them. The couple’s current studio was once a shared children’s bedroom, with a raised sleeping platform accessed by a ladder. The kitchen, living and dining areas were never formally separated, just loosely defined by levels, low walls and light. The materials are honest. The floor is quarry tile. The walls are white. A cast concrete base forms the structure of the sofa.

There are no expensive kitchen appliances, no showpiece staircase. The spaces are compact, with ceilings lower than many would now choose. But the proportions are generous in spirit. Light moves beautifully through the house. Every window feels positioned to catch a shadow, a branch, a change of season.

Nothing has been updated or reworked. Visiting now, it looks almost exactly as it did in 1971. That may be a matter of ethos, or practicality, or both, but it is unusually sustainable. Not just in terms of embodied carbon, but in resisting the cycle of fashion and reinvention that defines so much domestic architecture. It is still Peter and Margaret’s home. They are both in their nineties, still living there with quiet grace.

The garden

Many visitors come for the garden as much as for the house. Margaret began shaping it as soon as the house was complete, and she and Peter continue to tend it today. The garden is not a green buffer around the building, but a continuous architectural experience. It has rooms, thresholds, long axes, borrowed views, small moments of surprise.

Paths lead you through a sunny glade, a narrow box lined court, a shaded corner of brick and timber. A pergola leans under a vine. There is no grand lawn, no showy borders. But the planning is as careful as any formal garden. It is informal, yet composed.

Inside the house, the garden is always present. A low sill captures the texture of soil. A square window holds the shape of a fruit tree. The rooms open not just outward, but downward, into the planting. It feels, as Jane Brown wrote, like the house has grown there.

The garden is not ornamental, it’s integral. Designed alongside the buildings, it reinforces the orchard’s memory and shapes the rhythm of space and light across the site.

The garden demonstrates that landscape can be conceived not as decoration, but as a continuation of architectural intent.

A life’s work

Middle turn house & garden

Peter’s practice eventually moved into a converted building at the back of the site. He ran his studio there for almost 20 years, before growing tired of the industry. From then on, he focused on the garden and on securing Turn End’s legacy. The Turn End Trust was established in 2012 to protect the site and share it with the public. Events, open days and talks are now part of the life of the garden.

Middle Turn, one of the three houses, is now owned by a younger architect who worked for Peter as his first graduate job in the late 1980s. He recently bought the house and describes it as a dream come true. He opened his home for the open day and gave a spontaneous talk at the start. There was a quiet sense of continuity, younger architects stepping into a living tradition.

A house made for Haddenham

The houses are inseparable from their village. You cannot imagine them lifted and dropped into another site. Their scale, their geometry, their enclosure, all of it is shaped by the trees, the walls, the footpaths of Haddenham.

And yet, the principles behind them are entirely portable. The idea of responding to your exact context, visually, historically and environmentally, is not a nostalgic one. It is a modern approach, and a sustainable one. The houses feel contemporary even now, not because of their details, but because of their attitude.

Turn End doesn’t overwrite the village’s historic patterns, it responds to them. The footpaths, the enclosed garden spaces, even the sequencing of views feel rooted in Haddenham’s medieval grain.

Lessons for now

Many people today may want more space than Turn End offers: larger rooms, higher ceilings, and possibly richer more luxurious materials. But so many ideas here are still deeply useful.

The restrained palette, with just a few materials repeated inside and out, creates a strong and calming sense of identity. The stepped layout around a courtyard brings in daylight and privacy in equal measure. The flexibility of the plan means that differing inhabitants can use the house in different ways and still make it work for them. And the sense of containment, of garden and home as one organism, is something very few new builds achieve.

These ideas offer a powerful guide. They encourage a lighter touch, and a more sensitive response to place.

Why it still matters

The Turn End houses are compact, more like cottages than villas. Ceilings are low. Views are controlled, layered, discreet. Clerestory windows let in the light, but not the spectacle. There are no grand vistas. The garden wraps closely around, but it is not presented from a distance. It is present in fragments, glimpses, always there, but never fully revealed. This is a house that invites quiet attention.

And yet it is full of ideass, the kind of ideas that are as timely now as they were sixty years ago. The flow of space. The use of honest materials. The rhythm of garden and room. The possibility of building a life, slowly, in a place of your own making.

There is something very English in its restraint, but also something Japanese in its calm clarity. Nothing is wasted. Nothing is rushed. Turn End is not large, but it is complete. It is not luxurious. It is quiet, clever and alive. It shows that architecture can be gentle and radical at the same time. That gardens can be designed like buildings. That a house can remain the same but respond to the lives of its inhabitants, shaped by its owners and the world around it.

In resisting the lure of updates and fashion, the house remains deeply sustainable, not only in its materials, but in its durability, adaptability and resistance to obsolescence.

And somehow, that still feels like progress.

Information gleaned from my trip to the house and also from the excellent ‘a garden & three houses’ by Jane Brown with pictures by Richard Bryant which I bought at the open day.