Kenwood House: An architectural palimpsest

Hampstead Lane, London, NW3 7JR

Year first built: 1616

Rebuilt: 1779

Period: Georgian

Architectural style: Neoclassical

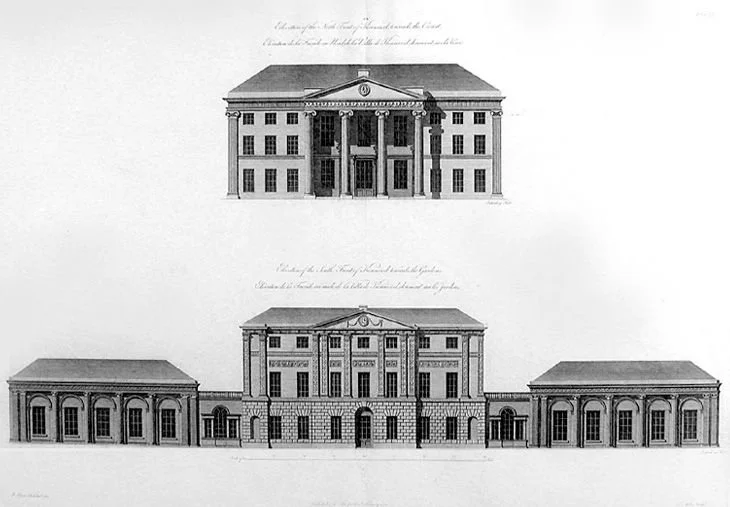

The south façade of Kenwood house

As part of our year exploring historic homes, Kenwood marks our fifth visit and perhaps the most personal one yet. I recently visited my local Kenwood House, a place I come back to often as I live nearby. Run by English Heritage and cared for by kind and knowledgeable volunteers, it is always a pleasure to walk through its rooms and notice new details. I thought I would share some of what makes it special, both for anyone who enjoys discovering London’s layered history and for those with period homes looking for ideas on how old architecture can be adapted and cared for over time. Kenwood is full of lessons in proportion, light and craftsmanship, and a reminder of how beautifully a house can evolve while keeping its character.

Kenwood’s South facing facade

Kenwoods’ history

Origins: Caen Wood

The land where Kenwood now stands was once known as Caen Wood, a name that goes back to the medieval period. From the 13th century it belonged to monastic orders, and the earliest record dates from 1226, when a William de Blemont granted his lands in “Kentistun” in the parish of St Pancras to the Priory of Holy Trinity, Aldgate. The grant was confirmed by royal charter from Henry III the following year. The estate then covered what is now Kenwood and Parliament Hill and was known as the Bishop of London’s park, or Hornsey Park. In 1525 it was divided, with the southern part covering Parliament Hill and the northern area known as Canewode Feildes. That northern land changed hands several times before being bought in 1616 for John Bill, King James I’s printer.

Jacobean beginnings

John Bill built the first house on the site, a red brick Jacobean home with a square plan, gabled roof and tall chimneys. The 1665 Hearth Tax recorded twenty-four hearths, so it must have been a generous house for its time. The Bill family owned it until 1690, when financial troubles forced a sale to Brook Bridges, a barrister who may have begun the first phase of remodelling.

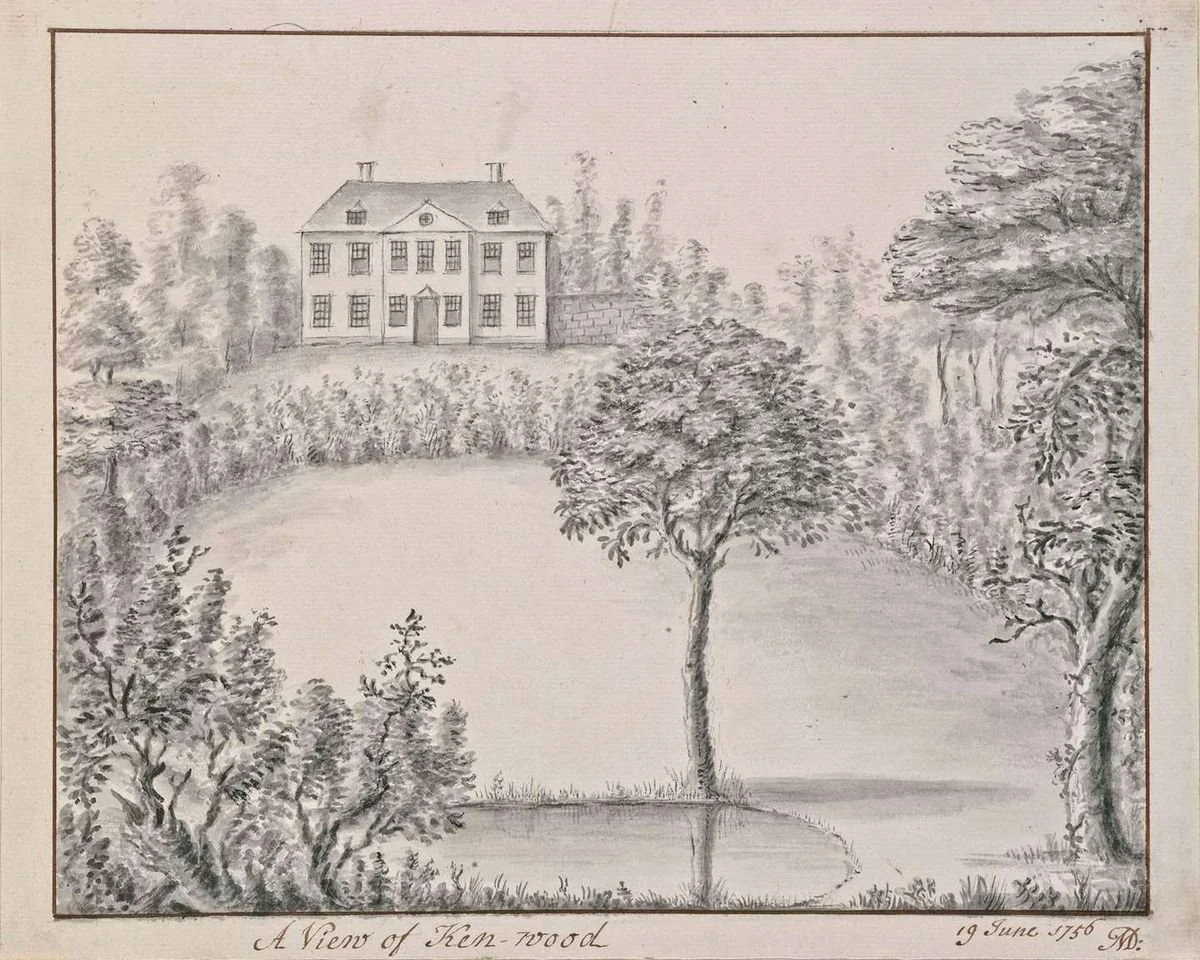

Mary Delany’s 1756 drawing

The early eighteenth century: Lord Harley and Georgian classical architecture

In 1694, the estate was purchased by the Harley family. It was Edward Harley, 2nd Earl of Oxford, a Tory politician who first commissioned major changes to the building. By about 1700, the house had become a more formal red brick residence with stone quoins, sash windows, and a hipped roof - remodelled with a new classical façade and a more regularised floor plan, in keeping with the emerging ideals of the English Baroque. The Harleys were bibliophiles and collectors, and under their ownership Kenwood began to reflect the intellectual and cultural ambitions of the English aristocracy in the early Georgian age.

Throughout the early 18th century, it passed through several owners, including the Earl of Berkeley and the Duke of Argyll. In 1746, the 3rd Earl of Bute, John Stuart, acquired the estate and made key landscape and botanical improvements, including the orangery to the west of the south front of the house and the introduction of exotic plants to the landscape. Mary Delany’s 1756 drawing shows a white-painted house, ‘double pile’ house painted white, with a steeply pitched roof and dormer windows. with dormer windows and a steep roof, marking the final phase before Adam’s transformation.

John Rocque’s 1746 map, map showing Kenwood before the formal gardens were removed

Lord Mansfield and the neoclassical transformation

Kenwood’s true transformation began in the mid-eighteenth century when in 1754, William Murray, later the 1st Earl of Mansfield and Lord Chief Justice of England, responsible for the success of the Somerset Case in 1772, the first legal step towards the British abolition of slavery in the 1830s. He purchased Kenwood for £4,000. (Having consulted with Chat GPT, this works out as £4,000 in retail price terms would be roughly £1–1.2 million today. But £4,000 in relative elite / economic power terms (comparable to a wealthy landowner or banker) could be more like £20–40 million today. - still much less than it would cost if it ever were to go on sale today I would imagine) He and his wife, Elizabeth Finch, used it as their country villa. Mansfield's legal brilliance and political stature eventually earned him an earldom and deepened his desire for a house that reflected his ideals and achievements. By 1764, he had commissioned Robert Adam to remodel the house. This marked Kenwood’s shift from a Jacobean manor to one of the most important neoclassical villas in Britain.

Adam’s work between 1764 and 1779 was not merely cosmetic. He reimagined the house from within. He added a striking new entrance portico, extended the north front with a dramatic central pediment, and created the magnificent library that still defines the interior today. He designed new state rooms, and transformed the south-facing elevation to accommodate attic bedrooms. Adam created rooms carefully tuned to the Enlightenment ideals of order and intellectual pursuit. The interiors are among Adam’s finest surviving work, particularly the library, or "Great Room," designed for entertaining and showcasing intellect. Other highlights include the drawing room, hall and staircase, decorated with elegant plasterwork and classical detailing. Adam claimed Lord Mansfield was an excellent client and partner in the design process and "gave full scope to my ideas."

The Great Room - also known as The Library by Adam

Kenwood also became the home of Dido Elizabeth Belle, Mansfield’s great-niece and the mixed-race daughter of a formerly enslaved woman. She was raised at Kenwood as a family member, a remarkable fact for 18th-century Britain.

The library created c. 1767 by Robert Adam for Lord Mansfield was one of the most deliberate architectural statements of the Enlightenment. It could function as a private retreat for legal preparation but it was equally designed for parties and events, where Mansfield would host judges, politicians, ambassadors and scholars. Looking at details like the mirrored arched niches along the hall one can imagine the clink of glasses and the play of light and reflections of important people socialising at Lord Mansfield’s event in this room.

Design of the Ceiling of the Library or Great Room at Kenwood

London: 5 February 1774. Engraving, coloured by hand, by B. Pastorini, source

The room was designed as an expression of neoclassical Enlightenment thinking. The light is carefully controlled, through the evenly set windows to ensure a steady, diffused quality suitable for reading and thinking. The ceiling is mathematically structured, with geometry used not merely for decoration but as a philosophical statement relating to ideals of the enlightenment .

The Great Room / Library’s delightful ceiling designed by Robert Adam

The mirrored arched niches add depth during the day time but at night during events they would have multiplied candlelight, movement and faces, creating a theatrical effect. While named a library, there are only bookshelves on the two ends of the room and the the books were chosen as much for rarity and continental prestige as much as one would imagine for reading. Really, this was a room to convey culture and power.

The Great Room (Library) at Kenwood House designed by Robert Adam

The nineteenth century: new wings

In the early nineteenth century, Kenwood passed to successive generations of the Mansfield family, who began to expand the house again. Kenwood passed to Mansfield’s nephew David Murray, the 2nd Earl, who added the north-east and north-west wings to house a new dining room and additional bedrooms between 1794 and 1796. These included the music room and dining room, designed by George Saunders, and a new service wing with kitchens and brewhouse. Later, in 1815, architect George Saunders was commissioned to make further changes. He added the iconic orangery and remodelled parts of the service wing, subtly adapting Adam’s neoclassical language for a new era.

An aerial view showing the extent of development of Kenwood house

The 2nd Earl also commissioned the famous garden designer Humphry Repton to reshape the landscape, introducing winding paths, concealed views, and woodland groves. The formal forecourt was replaced by the open Half Moon Lawn, giving the house a more naturalistic and picturesque setting. The additions are classically proportioned but more robust in character, a Regency sensibility beginning to edge into the earlier Palladian grace, balancing grandeur and calm, never tipping into ostentation.

Late Victorian and Edwardian economic threat

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Kenwood entered a period of risk not through neglect but through economic changes of the day. The late Victorian and Edwardian era brought a raft of new taxation legislation across Britain that targeted landowners. The 1894 Estate Duty Act introduced heavy inheritance tax on landed property. The 1909 People’s Budget further increased taxation on land and high incomes. These laws reflected a reforming Liberal government’s agenda. They effectively dismantled the financial model that had protected houses like Kenwood for centuries. There was a genuine risk that Kenwood would be sold for speculative redevelopment.

Edwardian tenants and Twentieth-century decline

By the early 20th century, Kenwood was rented out to aristocratic tenants, including Grand Duke Michael of Russia and later Nancy May Leeds, who married Prince Christopher of Greece. By the early twentieth century, the house was in decline. The 6th Earl of Mansfield, burdened by rising taxes and the cost of maintaining a large estate, sold Kenwood in 1917 to a speculator. The house contents were auctioned off in 1922, and by 1925, the future of the estate was uncertain.

The house at risk, rescue, and public legacy

During the First World War (1914–1918), Kenwood House was used as a military hospital, staffed by trained nurses and volunteers. The idea was proposed by Grand Duke Michael Mikhailovich of Russia, who leased the house at the time, together with Lord Mansfield. Wards were set up in the grand rooms, and convalescing soldiers were cared for amid Robert Adam’s delicate interiors a striking contrast that foreshadowed the house’s later role in national service.

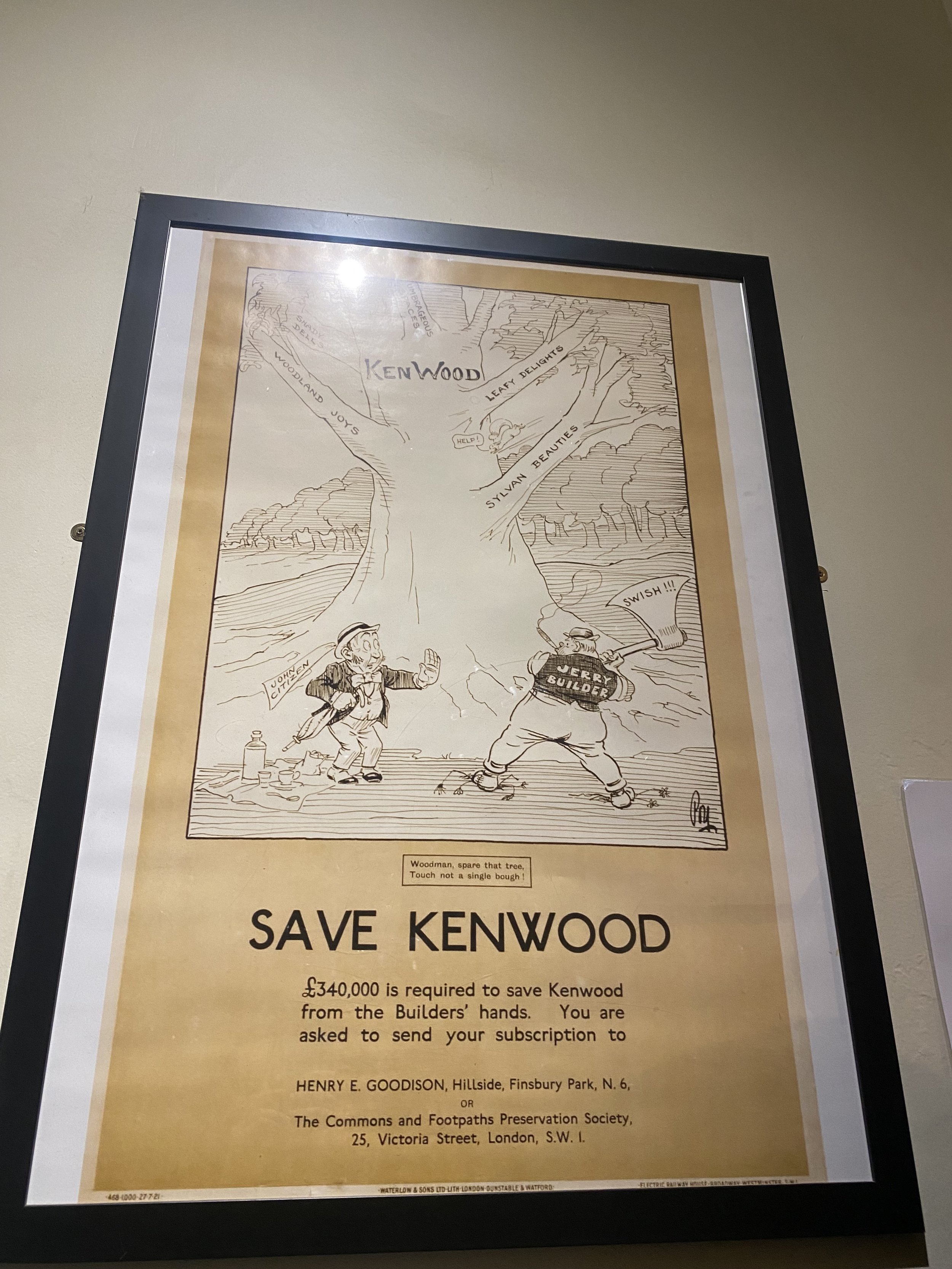

A few years later, the estate once again faced an uncertain future. In 1922, local residents and preservationists formed the Kenwood Preservation Council, determined to save both the house and its surrounding parkland from speculative building. A striking campaign poster from this period, now displayed in the café at Kenwood, captures the sense of public urgency and civic pride that fuelled their efforts.

By 1924, the Council had successfully purchased 74 acres, including the ponds and “Ken Wood”, and vested the land in the London County Council (LCC) to ensure its long-term protection.

The decisive turning point came in 1925, when Edward Cecil Guinness, 1st Earl of Iveagh, heir to the Guinness brewing fortune, purchased Kenwood House and its core estate. He also assembled a major collection of 63 Old Master and British paintings, including works by Rembrandt, Vermeer, Van Dyck, and Turner, which he intended to leave to the nation. His philanthropy not only saved the house from destruction but laid the foundation for its future as a public cultural treasure.

Following Lord Iveagh’s death in 1927, his will established the Iveagh Bequest (1929), which stipulated that Kenwood House should be kept open and free to the public, preserved as an example of a gentleman’s artistic home of the eighteenth century. The LCC (London County Council) , which already owned the surrounding parkland, was appointed to manage the property.

During the Second World War (1939–1945), Kenwood House was closed to visitors and used to safeguard works of art from the British Museum, evacuated from central London for protection from bomb damage. Parts of the estate sustained minor damage from air raids, and temporary wartime structures were erected in the surrounding grounds. The house reopened to the public after the war, continuing its role as both a cultural landmark and a place of refuge for national heritage.

From 1929 onwards, Kenwood House and its grounds became public property, administered by the LCC until 1965, when responsibility passed to the Greater London Council (GLC). After the GLC was abolished in 1986, English Heritage, newly formed as the national heritage body, took over the care and management of Kenwood House and the Iveagh Bequest.

A century after those early campaigns, Kenwood remains a rare example of a great house preserved for the public through civic action and philanthropy. A major restoration in 2012–13 returned Robert Adam’s interiors to their original colour schemes and improved the display of the Iveagh Collection, ensuring that both the architecture and art continue to be enjoyed in the spirit of Lord Iveagh’s bequest.

Inspiring details

I always spot new details every time I visit, some nice ones I noticed this time around.

Window seats

The windows on the ground floor are set deep into the thick walls, which creates these generous reveals where window seats naturally fit. In some rooms they’re built in as part of the panelling, and in others, like here, a freestanding bench has been placed in front of the window. You can imagine how lovely it must once have been to sit here, with the shutters open and light streaming across the patterned upholstery, looking out over the lawns. These spots would have been perfect for reading or quiet conversation, giving a sense of both comfort and connection to the garden outside. Sadly, because of the art collection, the blinds now have to stay closed to protect the paintings from sunlight, so the spaces feel a little dimmer than they would have in the eighteenth century—but the furniture and detailing still tell the story of how these rooms were once enjoyed.

Grand marble fireplaces

The three fireplaces on the ground floor are beautiful examples of late eighteenth-century neoclassical design and show Robert Adam’s talent for making classical detail feel light and graceful. Each one is carved in white statuary marble with delicate motifs of anthemion, acanthus leaves and small roundels along the frieze, their slender proportions drawing the eye upwards. The pale marble contrasts nicely against the dark metal inserts and fireboxes. The library fireplace, in particular, feels grander and more formal, with intricate panels of classical figures and borders so finely carved they could almost be mistaken for plasterwork. Its wider surround suits the generous scale of the room, and positioned beneath the portrait of Lord Mansfield.

2.Layered views through rooms

Large doorways can be looked through - framing and guiding the eye through multiple spaces.

Lord Mansfield’s bedroom - cupboards to either side - please see the floor plan below - to the right is apparently a secret staircase

Principal bedroom - Bed nook & a secret staircase

The room that was once Lord Mansfield’s principal bedroom is now used as an exhibition space, but it still holds a few intriguing traces of its original design. Set into one wall is an elegant arched recess created by Robert Adam to frame the four-poster bed, which would have been positioned neatly within it. To the right of the bed niche is what appears at first glance to be an ordinary cupboard, but it is in fact a concealed doorway leading to a narrow private staircase down to Lord Mansfield’s original dressing room at ground floor level (according to the helpful volunteer at English Heritage)This secret stair would have allowed Lord Mansfield to move discreetly between floors without using the main staircase or enabled his servants to come and go quietly to attend to him when the principal rooms were in use. Sadly I didn’t take a photo of this.

Lord Mansfield’s bedchamber - apparently the right handside cupboard leads to a secret stair that connects with his dressing room below

Oval rooflights over the staircases

Roof lights are commonly used now but in the 1700s they were rare and expensive to implement. The beautiful, delicate rooflight that sits over the main staircase is cleverly designed to be able to hold a chandelier from its centre. Set as a dome, it allows views through to the sky above and illuminates the stairwell below.

Standing beneath the oval rooflight above the main staircase, I was struck by how clever it is. It’s made entirely of glass framed in fine metal, with the ribs radiating from a central ring where a chandelier was designed to hang. In our projects, we often face restrictions when there’s a rooflight over a staircase or dining table, because it rules out any pendant lighting directly beneath. Here, the design solves that problem beautifully - the chandelier is suspended from the centre of the rooflight itself, allowing both daylight and what would have originally been candlelight to come from the same point. It’s such a clever solution.

Crafted staircase details

What’s lovely about this staircase is the level of craftsmanship in the individual elements. The treads and risers are solid timber with nosings that have softened with age. Each tread ends with a carved roundel where the step meets the string, which is a detail you often see in high-quality eighteenth-century joinery. The string itself is decorated with a continuous carved scroll motif, in painted timber.

The wrought iron balustrade is particularly fine. The individual upright spindles are hand-forged, with delicate waterleaf and anthemion patterns that tie the metalwork back to the neoclassical style of the interiors. The light blue paint, which I believe is Adam’s original colour softens the iron and helps it read as part of the room’s decorative scheme rather than something purely functional.

Decorative mirrored niches

The mirrored niches in the library bring depth, theatricality and liveliness to the space. I can imagine them allowing intriguing glimpses of interesting conversations during a busy party

The pretty bridge - a picturesque folly

The fake bridge

At the entrance to kenwood from Hampstead Heath lies a fake bridge, designed to complete the picturesque view from the house over the pond but in fact it is just a facade. However, I spoke to local woman who said that as a child she would climb across it!

Final Thoughts

Every time I visit Kenwood I am struck by how gracefully it has adapted over the centuries. Each generation has added something of its own, with new rooms, new ideas and new ways of living, yet the house still feels whole. It is a lovely reminder that old buildings do not have to be frozen in time; they can evolve while keeping their character intact.

That balance between care and change is something we think about often in our own work. Whether it is a listed townhouse or a family home with a long history, the aim is always the same: to understand what makes a place special and let it shine again. Kenwood shows just how beautifully that can be done.