Taxes and the quirks of Victorian and Georgian architecture

We love working with historic homes and start each project by uncovering the history of the property, allowing us to sculpt a design that responds to the quirks of the house and tells its story. That begins with the wider history of the street and neighbourhood, and then the specific background of the house itself. Every building has its own unique attributtes, and understanding them allows us to design in a way that feels right for that particular place. Over the years we have noticed certain patterns repeating themselves, details that appear again and again across Georgian and Victorian houses. When we looked more closely, many turned out to have the same surprising origin: historic taxes. Taxes are something that dominate lives today (see our earlier blog on VAT and building your home) and Georgian and Victorian Britain was no different. This blog post looks at the Georigan and Victorian taxes on windows, glass and bricks shaped the architecture of the time, producing some of the most notable features of buildings from this time

The window tax

Albert Street, Bloomsbury, NW1 - built in the 1840s while the window and glass tax were still in effect. People would rather block up their windows than pay the exorbitant taxes involved.

1696 - 1851

The window tax was introduced in 1696 during the reign of William the Third. England was fighting the Nine Years War with France and the king needed to find a way to fund the conflict. Income tax as a concept had not yet been thought of, and the previous hearth tax had been abandoned because it required inspectors to enter people’s homes. Windows provided a practical alternative since they could be counted from the street. The principle was straightforward. The more openings a property had, the higher the annual duty, turning light and air into a visible measure of wealth.

For the wealthy with large country houses the charge was manageable, though even they sometimes blocked or reduced openings. For the middle classes in London who bought speculative terraces, the cost could be punishing. A typical Third Rate House of the 1820s with 17 windows might be charged around £8 and 14 shillings, which is roughly £1,270 in today’s money. If the design included a pair of canted bays, increasing the total to 21, the duty rose to £12 and 1 shilling, about £1,760 in modern terms. The difference of nearly £500 a year helps explain why speculative builders avoided features that increased liability.

The effect was profound. Blocked windows are still visible across Georgian and early Victorian streets, their outlines clear in mismatched brickwork or subtle changes in render. Blind windows, painted or recessed to maintain symmetry, became fashionable, even though many were never intended to open. Staircases often have single tall windows where two or three smaller ones would have been expected. These minimised the tax burden but weakened walls structurally and did little for ventilation.

By the 1840s critics were vocal. The Builder, a leading architectural and construction magazine of the nineteenth century complained in 1844 that Parliament had effectively told builders to design houses with as few openings as possible. The result, it said, was unhealthy homes with dark interiors and poor air quality. Streets such as Gower Street in Bloomsbury, built with long runs of flat fronted terraces and minimal ornament, were singled out as dull and gloomy thoroughfares.

The window tax was eventually repealed in 1851, during the reign of Queen Victoria.

The glass tax

1746 - 1845

The glass tax was introduced in 1746 under George II, at a time when Britain was looking for ways to raise money in the aftermath of the War of the Austrian Succession. Like the window tax before it, the levy was designed as an indirect way to raise revenue at a time when income tax did not exist. The duty was charged by weight, which made large sheets of glass prohibitively expensive. As a result, Georgian windows were divided into many small panes. The familiar six over six sash, with its heavy glazing bars, was not simply a stylistic choice but an economical response to taxation.

Six over six sash windows at our Our Georgian Grade II listed house, in Dartmouth Park, NW5 - built in 1805

When the tax was repealed in 1845 during Queen Victoria’s reign, the change was immediate. Suddenly larger sheets could be manufactured and afforded. Window design shifted towards fewer panes with slender glazing bars, producing the elegant two over two sash that we now associate with Victorian houses. Shopkeepers quickly embraced plate glass, creating the wide display windows that transformed high streets. Large single panes also encouraged the design of conservatories and winter gardens, which flourished in the mid nineteenth century.

The brick tax

1784 -1850

Gower Street, WC1 - built in the 1780s. People complained at the time about what they considered to be its flat repetitive façades that were the result of the brick tax

The brick tax was introduced in 1784, during the reign of George III (1760–1820). It was brought in after the costly American War of Independence (1775–1783), which had left Britain with heavy debts. Parliament looked for new ways to raise revenue, and bricks essential to the rapidly growing towns and cities of the late eighteenth century, were an obvious target.

.A third levy, the brick tax of 1784 to 1850, influenced construction in more subtle ways. Charged per brick, it encouraged manufacturers to produce larger bricks to reduce numbers. It also made builders wary of features that consumed more material. Complex chimney stacks, decorative string courses and projecting bays all became rare. The aesthetic shifted towards flat fronted terraces with minimal ornament.

The tax lasted until 1850, when it was repealed under Queen Victoria, just a year before the repeal of the window tax. When the brick tax was repealed, the effect was immediate. Chimney stacks became more elaborate again, polychromatic brickwork appeared in the hands of architects such as William Butterfield, and façades regained depth through mouldings, banding and decorative courses. Builders were once again free to play with colour, pattern and relief in brick.

The return of the bay window

When the taxes on glass, bricks and windows were lifted in the mid nineteenth century, the bay window returned with enthusiasm. First seen again in detached villas, bays quickly migrated to terraces, and by the mid 1860s they were almost universal.

The canted bay, with angled sides, became the defining form. It brought oblique views up and down the street, and it poured light into the front drawing room, which was the social heart of the house. These projecting forms also added variety to what had previously been monotonous runs of flat fronted façades.

By the 1880s, builders had begun adding bays to the sides of rear extensions to brighten middle rooms that had long been dark. What had once been too costly for half a century became a sign of comfort, prosperity and modern living. Today, bay windows remain one of the most recognisable and loved features of the Victorian house, both practical and decorative, with a strong precedent for reinstatement or sensitive alteration.

Our Kensington House built in the 1860s has bay windows which allow a lovely views in front of the house and to both sides

Taller, larger sash windows

The repeal of the glass tax in 1845 made it affordable to produce large panes, and window design changed almost immediately. The small paned Georgian sash gave way to the elegant two over two sash with slim glazing bars. In grander houses, these sashes often reached from floor to ceiling, opening onto balconies or gardens and blurring the boundary between inside and out.

This shift dramatically increased the amount of daylight reaching interiors. Drawing rooms and dining rooms became brighter and more gracious. Even modest terraces benefitted from larger panes, which allowed for a lighter, more modern feel.

Our Primrose Hill Grade II listed townhouse in NW1 was built in the 1850s just after the glass tax was repealed - note the two over two sash windows.

Plate glass shopfronts and garden rooms

The fall of the glass tax also transformed the public face of buildings. High street shopfronts embraced plate glass, creating wide transparent façades that invited customers in. This new technology gave birth to the modern shop window and forever changed the look of commercial streets.

In domestic architecture, large panes encouraged a new taste for garden structures. Conservatories and winter gardens flourished, often attached to villas as elegant glass rooms filled with plants. The idea of a light filled space overlooking the garden, so common in today’s extensions, can be traced back to this moment when large sheets of glass became affordable.

Artistic Impression of a Paxton style Victorian Conservatory created by NGA that would have been built after the repeal of the glass law

Decorative brickwork and bold façades

Polychromatic brickwork at St. Pancras Station & Hotel by Sir George Gilbert Scott built in 1868 - photo taken by George P Landow

The brick tax, in force from 1784 to 1850, had made builders wary of ornament. Charged per brick, it penalised features that required more material and encouraged a plain, economical style. When it was repealed in 1850, façades quickly regained richness.

Elaborate chimney stacks reappeared, decorative string courses and mouldings returned, and façades gained depth. Architects began to experiment with colour and pattern, leading to the polychromatic brickwork of figures like William Butterfield. Even ordinary speculative terraces acquired more character through varied bonding, ornamental arches over windows and the confident projection of bays.

Reading these traces in your own house

For a present day homeowner these fiscal ghosts are not just curiosities but practical clues.

Blocked windows often mark where an opening was sacrificed to save tax. If the outline is still visible, reinstating it can restore symmetry and improve light. Conservation officers are sometimes supportive when evidence of an original sash can be demonstrated.

Blind windows were usually deliberate, designed to preserve balance while avoiding the cost of glazing. These are best respected as part of the architectural grammar.

Glazing patterns should reflect the period. Six over six sashes with small panes belong to the Georgian era of glass taxation. Two over two sashes with larger panes are typical of later Victorian houses once large sheets became affordable.

Bay windows remain one of the most effective ways to transform both interior quality and street presence.

Tall external French doors After the repeal of the window tax in 1851, openings could be enlarged without penalty, paving the way for tall French doors that reached almost to the floor. These doors often opened onto balconies or gardens, flooding rooms with light and connecting interiors more directly to the outside.

Decorative fanlights During the glass tax, fanlights above front doors were usually modest, divided into many small panes to keep costs down. Once the duty was lifted in 1845, more elaborate and decorative fanlights became affordable, with graceful patterns of curved and radiating glass that added distinction to front entrances.

Polychromatic brickwork The brick tax of 1784 to 1850 discouraged ornamental detail since every additional brick meant extra cost. Its repeal allowed architects to experiment again, and the mid-Victorian period embraced bold polychromatic brickwork, combining colours and patterns to give façades richness and character. The Frognal area in Hampstead in the borough of Camden has many wonderful examples

Final words

The story of these taxes explains why some Georgian streets feel austere, why so many early Victorian terraces have blocked sashes, why glazing patterns shifted, and why later Victorian terraces erupted with confident bays and generous glass. For today’s homeowner it adds richness to the story of the house and provides guidance for sensitive restoration and adaptation.

Design is never the result of taste alone. It is shaped by rules, by economics and by the creative ways in which people respond. The window, glass and brick taxes remind us that even the quirks of a façade can carry the memory of centuries of policy, ingenuity and the simple human desire for light.

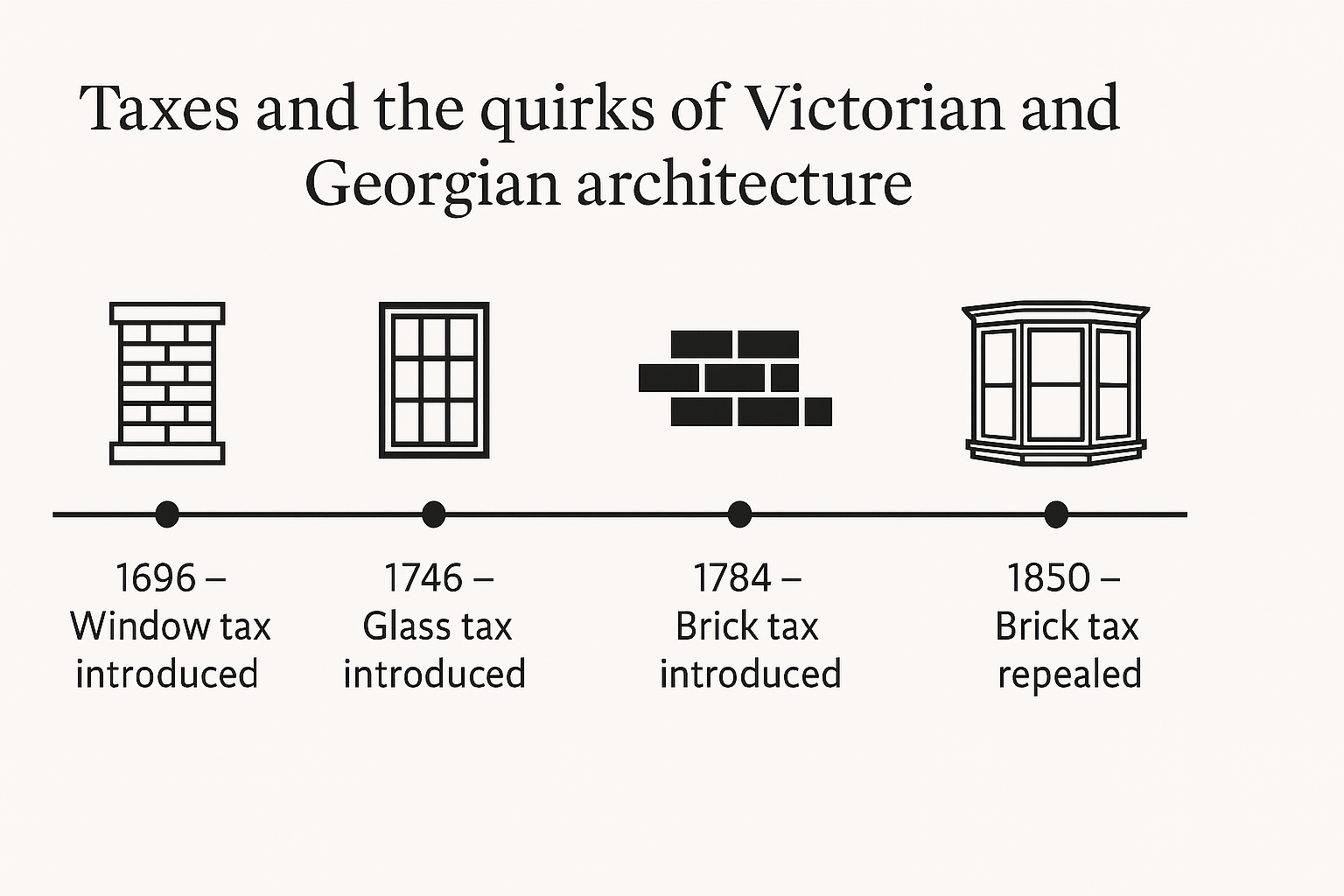

Key dates and their architectural effects

1696 – Window tax introduced. Homes taxed on the number of openings. Blocked windows and blind windows appear across Georgian streets.

1746 – Glass tax introduced. Charged by weight, it makes large panes expensive. Six over six sashes with many small panes become the norm.

1784 – Brick tax introduced. Charged per brick, it encourages larger bricks and discourages decorative features. Terraces take on a flat, austere look.

1845 – Glass tax repealed. Large panes become affordable. Two over two sashes spread rapidly, shopfronts transform with plate glass, and conservatories grow in popularity.

1850 – Brick tax repealed. Builders return to ornament. Decorative string courses, patterned façades and elaborate chimneys reappear.

1851 – Window tax repealed. Bay windows come back with confidence, French windows and tall sashes flourish, and streetscapes grow lighter, more varied and more expressive.

If you have a historic property you are thinking about refurbishing, extending or restoring and would like some advice, please do get in touch, we would love to help.